Mean Reversion:

Lessons from Liverpool’s 2020 Title Win

By Anthony Corrigan

July 2020 Read Time: 20 Min

Key Points

- Liverpool Football Club has finally ended its three-decade wait for a league title by winning the 2019/20 English Premier League season. This long-awaited achievement provides a constructive reminder and a welcome comfort to the weary value investor.

- Both football fans and equity investors should remember that dry spells for all teams/strategies are to be expected and that extrapolating recent performance into the future can be a costly mistake. What hasn’t worked for some time should not be presumed dead!

- Disruption has been commonplace in both football and equity markets for many decades. The ‘top dogs’ are constantly changing and a strategy that over-allocates to these expensive positions will likely suffer as a result.

- Liverpool’s success in recent years demonstrates both the importance of valuation and the effectiveness of a conservative investment approach (i.e., growing a business in a sustainable manner). The importance of strong leadership and a supportive culture should also not be underestimated.

A very important illustration of long-horizon mean reversion has happened in the world of football (or soccer, as my American colleagues call it) that deserves special attention. Liverpool Football Club, one of the game’s most iconic names, has reclaimed the top spot in English football by winning its 19th league title. As the now infamous quote goes, Liverpool ‘are back on their perch’.

It has been a long wait for Liverpool, an agonising 30 years and almost two months to be exact. While painful to endure, Liverpool supporters never lost faith; almost every new season was greeted with an unrelenting optimism that this could finally be their year. ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, a song synonymous with Liverpool, conjures up emotions of perseverance, courage, and strength with the lyrics ‘When you walk through a storm, Hold your head up high, And don’t be afraid of the dark’. This spine-tingling anthem epitomises all of the attributes necessary to stand against the crowd and keep faith when others are losing theirs.

Contrarian investors are, without doubt, walking through their own storm at the moment and could easily feel as if they are walking alone. The weary and wounded value investor, however, can take comfort from Liverpool’s journey back to the pinnacle of the English game.

It Hasn’t Worked in So Long, It Must Be Dead!

Until last week, Liverpool football fans would be forgiven for thinking they were destined never to regain the title. The COVID-19 pandemic had interrupted the groundbreaking season, coupled with the danger the season could even be rendered null and void, wiping all of Liverpool’s clear dominance from the record books. When the club secured its 18th and last league title in 1990, it was by far the most successful team in English football. The 1970s and 1980s represented a golden period of dominance for the club and many would not have envisaged such a long drought before it reclaimed the top spot.

Indeed, as a nine-year old boy who idolised the Irish players of that winning team (Steve Staunton, Ray Houghton, Ronnie Whelan—another Irish great, John Aldridge, had just left Liverpool for Spain earlier that season), I fully expected Liverpool to show up the following season and reclaim the title—but that, of course, never happened. Nor did it happen the following season or the season after that. Liverpool, the winning strategy in football for decades, had finally stopped working.

What happened to the club in the interim period? Is it correct to say Liverpool’s strategy had stopped working and was no longer a winner? Certainly, the team faced headwinds. New teams and strategies emerged that were deemed superior, and the club confronted the daunting prospect of entering administration in 2010, before the current owners, Fenway Sports Group (FSG), stepped in to save it from such an embarrassing fate.

Similar to a mistake we see too often in the world of equity investing, far too many who looked at Liverpool’s recent losing past extrapolated the same performance into the future, ultimately coming to an unfair conclusion. Long dry spells are not unusual and should be expected. Indeed, many forget that Manchester United, the team that pushed Liverpool aside to dominate the English game in the 1990s and 2000s, endured its own 26-year dry spell from 1967 to 1993 without capturing a league title.

'The weary and wounded value investor can take comfort from

Liverpool’s journey back to the pinnacle of the English game'.

We see similar trends in equity markets. Comparable to Manchester United, US small-cap equities had a dry spell of 26.7 years between 1983 and 2010. Intriguingly, low beta in the United States last peaked in the same year as Liverpool (1990) and continues to be underwater from that lofty position. Momentum investing remains underwater following its dramatic fall from grace in late 2008 (over 11 years) and high profitability is clamouring to get back to the highs it reached in 2012.

Today, the strategy getting the most attention for underperformance is value given its struggles over the past 13 years in which growth has significantly outperformed. Does this mean that value strategies no longer work? The simple answer is ‘no’. In the recent article ‘Reports of Value’s Death May Be Greatly Exaggerated’ (2020), my colleagues (Arnott et al.) argued that value investing has continued to produce what we call structural alpha1 despite the revaluation headwinds it faces. And although many industry prognosticators argue that value investing is dead, we can prove it is alive and kicking!

The following chart illustrates this very point by comparing the evolution of the value premium (solid line, left axis) with the value–growth relative valuation (dotted line, right axis). The value premium is calculated as HML (high minus low) following Fama and French (1993). HML measures the performance of a high (value) minus low (growth) long–short portfolio, which is balanced by size.

The relative valuation is the ratio of book value to price (B/P) for the growth portfolio to the B/P for the value portfolio. If the B/P of the growth portfolio is 0.4 and the B/P of the value portfolio is 2.0, then the relative valuation is 0.20. The median relative valuation is 0.21, which means that growth stocks are, on average, about five times more expensive than value stocks when measured by B/P. As the chart shows, however, the relative valuations of value and growth stocks have fluctuated widely over time.

When we plot performance and revaluation together in one chart, the short-term movements of the two appear to be joined at the hip. In the short run, the revaluation component (changes in the B/P of value relative to growth) is the dominant driver of the value portfolio’s performance relative to growth. Over the long run, however, the two diverge. This divergence suggests that the value premium is driven by structural alpha and is not just a lucky discovery due to a highly transitory revaluation component.

During its most recent dry spell, which starts at point D (July 2007) and runs to point E (March 2020), the value factor lost a cumulative 50.0% in performance, or −5.4% a year. From July 2007 to March 2020, the relative valuation moved from 0.23, which is relatively expensive at the 23rd percentile of the distribution, to 0.09, in the bottom percentile. At the current valuation level, growth stocks trade at about 11 times the average valuation of value stocks. The relative valuation has been close to this level only in two episodes over the nearly 57-year history of our analysis: the peak of the dot-com bubble (point C) and the nadir of the global financial crisis. Our decomposition indicates that the change in the relative valuation from point D to point E translated into a reduction in performance of −6.6% a year and turned a positive 1.1% structural alpha into the −5.4% a year realized value premium.

Let’s take a moment to think about Liverpool in this performance–valuation context. At the point of Liverpool’s last league title in 1990, the club had won twice as many league titles (18) as the 9 won by Arsenal and their Merseyside neighbours, Everton, whereas their great rival, Manchester United, had only won 7 titles. Liverpool was certainly trading expensively at that point in time (analogous to point D in the performance/relative valuation chart).

'We can prove that value is not broken: its return engine

has been producing positive structural alpha'.

The subsequent headwinds the club faced with both the re-emergence of old rivals and the emergence of new ones—culminating in the threat of administration in 2010—can be compared to value’s journey from points D to E (Liverpool football club went from relatively expensive to historically very cheap). This journey served to swamp all the structural alpha achieved—which in Liverpool’s case were the other major trophies won by the club.2

Both football fans and value investors are teased from time to time by promising rainclouds that remain resolutely on the horizon. Liverpool came close to ending its drought on many occasions with second-place finishes in 1990/91, 2001/02, 2008/09, 2013/14, and, of course, last season (2018/19) when the team finished an agonising one point behind the eventual winners, Manchester City.3 At this point, rival fans basked in the glory that this was the proof they needed—Liverpool would never again win the title.

Value investing’s woes appeared to break in 2016 when the style came roaring back briefly, only to resume its underperformance versus growth. As with Liverpool last season, these ‘nearly’ moments make it easy to condemn a strategy (football or investing) and to pile on to the narrative that it’s dead. Liverpool’s domination this season serves to demonstrate that positions can reverse very quickly!

It’s Different This Time

A common argument, and honestly a fair one, it always is different. Football changed significantly with the creation of the Premier League in 1992. The money available to the top football clubs ballooned, making the English Premier League the richest in the world. The Premier League’s newfound riches attracted the attention of some of the world’s wealthiest people interested in owning their very own football club.

In 2003, the Russian multi-billionaire Roman Abramovich bought Chelsea Football Club, and has invested to date a reported £1.25billion. The investment is certainly steep, but has proved successful. Chelsea ended its 50-year dry spell in 2005 to win what was, at that time, only its second league title. The team earned further titles in 2006, 2010, 2015, and 2017, along with many other major honours, such as the UEFA European Champions League in 2012.

Chelsea’s change of fortune was a significant development in the English game. The game’s biggest names had been disrupted—and the disruption didn’t stop with Chelsea. Manchester City, the long-suffering neighbour of Manchester United, was acquired in 2008 by Sheikh Mansour, a member of the Abu Dhabi royal family. Following Mansour’s significant investment—rumoured to be even higher than the amount Abramovich has poured into Chelsea—Manchester City won in 2012 what was, at that time, only their third league title, and ended their own 44-year drought. They added further titles in 2014, 2018, and 2019 along with other domestic honours in the FA and League cups, including a domestic treble in 2019, a first in the English game.

What many forget is that although disruptors obviously disrupt, they also get disrupted! Over the course of the last 30 years, the football league has witnessed a series of disrupters. First Liverpool was disrupted by Manchester United, who was, in its turn, disrupted by Arsenal, Blackburn Rovers (very briefly in the mid-1990s), Chelsea, and Manchester City. It is now seven years and counting since Manchester United last won the Premier League title.

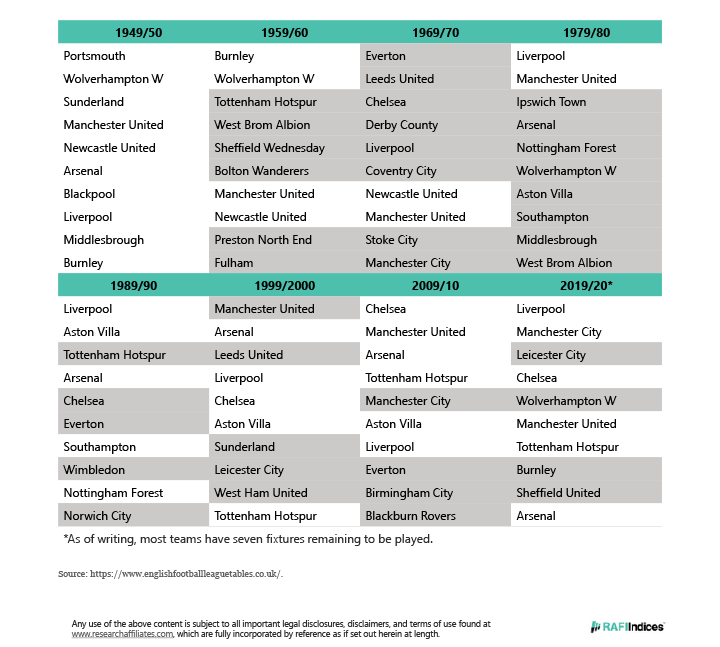

This trend has been evident for decades. An analysis of the top 10 teams in the English top-flight at the end of each decade-ending season since the 1950s vividly demonstrates this pattern. The teams highlighted in grey in the following table are the new entrants to the top 10 since the previous decade. The least amount of change is four teams (2009/10) with a high of eight teams (1969/70 and 1979/80). Certainly, the odds are very good there will be further changes and new entrants by the time we reach the conclusion of the 2029/30 campaign. If Newcastle United finds a new wealthy owner, could it make a comeback?

Rob Arnott, Vitali Kalesnik, and Lillian Wu conducted a comparable analysis in their article ‘Buy High and Sell Low with Index Funds!’ (2018) of the ‘top dog’ stocks (i.e., the 10 largest stocks in the world each year by market capitalisation). In a strikingly similar pattern, they demonstrated that the largest companies in the world are constantly changing and that a strategy, such as a passive market-cap index that over-allocates to these expensive stocks, is bound to underperform as the index rebalances into winners and out of losers. Conversely, strategies that ignore market prices and allocate to companies based on their fundamental accounting metrics tend to outperform over the long term.

Disruptors often become overly powerful and almost monopolistic in nature, traits that jump to the attention of regulators. In February 2020, Manchester City was fined and banned from the UEFA Champions League for two seasons due to alleged breaches of financial fair-play rules (the club is currently appealing this decision). Chelsea was also fined and banned from signing any new players over an entire transfer window as a penalty for breaching rules on signing youth players. The world’s largest companies can also be expected to face headwinds of increasing regulatory scrutiny in the years ahead, just like the top dog companies of the past.

Empire Building Beats Conservative Investment

Many market participants would have us believe that empire building beats conservative investment. The evidence clearly suggests otherwise. My colleague Vitali Kalesnik and his co-authors recently examined a number of metrics commonly used as a proxy for quality to determine which are robust and can generate a return premium for investors. In their Graham and Dodd award-winning article ‘What Is Quality?’ (2019), they showed that the quality definitions of earnings stability, capital structure, and growth in profitability are not associated with superior performance. They found, however, that the combination of high profitability and low investment (in other words, businesses that grow sustainably) provided strong evidence of an historical equity premium.

Do any of these traits show up in how Liverpool has been managed over the last 10 years? The answer is ‘yes’. In 2010 when FSG bought the club, Liverpool would have been considered a value stock in the world of football. The club was on the brink of administration and seemingly miles behind its competitors both on and off the pitch. In the true spirit of a value investment, FSG bought at ‘peak fear’ at what now appears to be a bargain price of around £300 million. In May 2019, Forbes estimated the club was worth approximately £1.7 billion, a multiple of more than five times the original price paid. The Deloitte Football Money League placed the club seventh in world football in 2020 with revenues of over €600 million (or over £550 million). That’s a remarkable turnaround for a club not so long ago standing at the brink!

Valuation clearly mattered to FSG when purchasing the club and they have followed a policy of conservative investment. In fact, over the last five seasons Liverpool’s net spend (fees paid for new players minus fees received from player sales) is over five times less than that of their biggest rival, Manchester City.4 Fans often dismiss net spend, but they shouldn’t because football is a business and businesses should live within their means to grow sustainably. Sceptics will point out that Liverpool made some marquee signings during the summer of 2018, and this is true. These transfers were only made, however, when the club could finally afford to do so, and player sales helped recoup a large chunk of the fees paid (in particular, the £140m fee received for Philippe Coutinho when he transferred to Barcelona in January 2018).

'Value is trading at an historically low discount to growth (100th percentile compared to its history) and even a conservative level of mean reversion could result in significant outperformance'.

In addition to a sensible transfer policy, FSG delivered on a long-awaited promise for Liverpool fans by developing the iconic Anfield stadium and increasing capacity to around 55,000 spectators with plans to add even more seats. This investment allowed Liverpool to catch its rivals in terms of match-day revenue. Liverpool also signed profitable sponsorship deals (including a new kit deal with Nike that begins in the 2020/21 season), and its growing success on the pitch garnered the club a healthy proportion of the lucrative TV revenue.

Liverpool’s new owners also did what many football clubs rarely do—plan for a future of organic growth by building a new state-of-the-art training facility to focus on training the youthful academy and established players together, with the goal of aiding the younger players’ development. The impressive Trent Alexander-Arnold, at 21 years of age, is an outstanding example of the rewards Liverpool is reaping through its investment in its next generation.

Some might believe FSG was simply lucky and be tempted to dismiss the owners’ deliberate decisions to buy at peak fear and invest conservatively. Bear in mind that FSG are the same owners that ended the ‘Curse of the Bambino’ when their Boston Red Sox baseball team finally won the World Series in 2004, ending an incredible 86-year drought—and Liverpool fans thought they had it bad!

On the pitch, the owners made what was without doubt their best decision when they recognised the need for strong leadership. Jürgen Klopp, the charismatic German coach, arrived on Merseyside in 2015 to turn the Liverpool faithful from ‘doubters to believers’. He set about his task by focusing on the culture and mental strength of his players. In keeping with the FSG approach, Klopp made no immediate lavish signings or significant outlays. His clear focus was on his current group of players, instilling in them a belief they could win and an ethos of hard work. He added resources incrementally, but only when he identified a good team player with the right attributes.

Building a strong culture and bond with his players was a critical part of Klopp’s plans, similar to a strategy we also feel passionately about at Research Affiliates. Indeed, our CEO, Katrina Sherrerd, documented her thoughts on the importance of culture in the article ‘The Winning Formula: Mission + Culture + Team’ (2019). Hiring people with the necessary skills and immersing them in a cognitively diverse group is crucial, but alone it will not guarantee success. To achieve a win-win-win outcome for our clients, our partners, and our employees, Katrina (or Katy, as many know her) emphasised that an organisation’s culture must value collaboration, equality of contribution, and cohesiveness in support of team decisions.

As the record shows, Klopp’s emphasis on team culture produced a winning outcome before he came to Liverpool. As the Borussia Dortmund manager, he led the club to back-to-back Bundesliga titles along with a German cup and a Champions League final appearance. Klopp’s Dortmund team of 2011/12 is still the last team outside of Bayern Munich to win the Bundesliga title.

Liverpool (and Value) to Dominate in the Years Ahead?

No doubt more trophies are in store for this Liverpool team. And as Liverpool has now ended its 30-year drought, the clock will continue to tick ominously on the dry spells other clubs are currently experiencing. Arsenal immediately springs to mind with a 16-year hiatus from the top prize. Does this mean Arsenal is a strategy that no longer works? Absolutely not. The club has a promising new coach and a gradual resurrection of its fortunes is a reasonable prospect if fans and management are both sensible and patient.

We must remember that dry spells are to be expected, even for strategies that have been proven to work over many decades. When dry spells end, however, they can do so in spectacular fashion—similar to what we witnessed with Liverpool’s record-breaking dominance this season.

With regard to value, as explained in ‘Our Investment Beliefs’ (2014), we at Research Affiliates firmly believe the largest and most persistent active investment opportunity is long-horizon mean reversion. While it has been without doubt a difficult period for value-oriented strategies, we firmly believe value will return a premium to the patient investor and to those investors who recognise the current opportunity and are brave enough to stand against the crowd and grasp it. Why are we so confident?

First, as stated earlier, we can prove that value is not broken: its return engine has been producing positive structural alpha. Second, value is trading at an historically low discount to growth (100th percentile compared to its history) and even a conservative level of mean reversion could result in significant outperformance. We have experienced this level of dramatic divergence between value and growth in the past, such as at the peak of the tech bubble—and we all know how that ended. Finally, our findings published in a new article ‘Value in Recessions and Recoveries’ (2020) demonstrate that value has significantly outperformed in market recoveries following previous recessions accompanied by bear markets.

For now, Liverpool fans throughout the world will rightly forget about the near misses and disappointments of the past, and while basking in the moment’s glory, will have no desire to contemplate the inevitable dry spells of the future. As the beloved Liverpool anthem goes, ‘At the end of a storm, There’s a golden sky, And the sweet silver song of a lark’. Value investors will be hoping for a similar outcome to their own storm in the not-so-distant future.

Webinar: RAFI in a Growth-Dominated Global Market (Replay)

RAFI Indices: A New Evolution of Smart Beta

Learn More About the Author

Endnotes

- Structural alpha is the component of the past return delivered net of any impact from rising valuations.

- Liverpool trophies after 1990 included two UEFA European Champions Leagues (2004/05 and 2018/19), three FA Cups (1991/92, 2000/01 and 2005/06), four League Cups (1994/95, 2000/01, 2002/03, and 2011/12), one UEFA Cup (2000/01), three UEFA Super Cups (2001, 2005, and 2019), and one FIFA Club World Cup (2019). The club throughout this time has been, over most periods, the most successful English club in terms of major trophies won. As of this writing, Liverpool has won 48 major honours in comparison to Manchester United’s 45. When the Charity/Community Shield and Football League Super Cup are included (widely accepted not to be major trophies), Liverpool has won 64 trophies compared to Manchester United’s 66.

- Liverpool’s tally of 97 points was the highest ever recorded for a team that did not win the title.

- Source is https://www.transferleague.co.uk/premier-league-last-five-seasons/transfer-league-tables/premier-league-table-last-five-seasons.

References

Arnott, Robert, Campbell Harvey, Vitali Kalesnik, and Juhani Linnainmaa. 2020. ‘Reports of Value’s Death May Be Greatly Exaggerated’. Research Affiliates Publications (May).

Arnott, Robert, Vitali Kalesnik, and Lillian Wu. 2018. ‘Buy High and Sell Low with Index Funds!’ Research Affiliates Publications (June).

Brightman, Chris, James Masturzo, and Jonathan Treussard. 2014. ‘Our Investment Beliefs’. Research Affiliates Fundamentals (October).

Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. 1993. ‘Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stocks and Bonds’. Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 33, no. 1 (February):3–56.

Hsu, Jason, Vitali Kalesnik, and Engin Kose. 2019. ‘What Is Quality?’ Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 75, no. 2 (Second Quarter):44–61.

Kalesnik, Vitali, and Ari Polychronopoulos. 2020. ‘Value in Recessions and Recoveries’. Research Affiliates Publications (June).

Sherrerd, Katrina. 2019. ‘The Winning Formula: Mission + Culture + Team’. Research Affiliates Publications (January).